Bravobo

Friday, May 26, 2006

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Matter becomes the matter of words, which creates structure, makes legible, interprets, against a ground of unreadable silence.

We know of silence only what words can tell us. Whether you like

it or not, we ratify only the word. (F 45)

Edmond Jabes

Robert Ryman·essay by Anne Rorimer

Robert Ryman's lifelong inquiry into the notion of painting as a medium and a verb—that is, into paint as a viscous material that articulates its support—began as early as the mid-1950s. His principal concern over the decades has been with the presentation of a painted surface in relation to its underlying support. This ongoing investigation has yielded ever-new visual possibilities, however nuanced these may be.

In Ryman's oeuvre the work's "image" results from the nature of the surface that arises when paint is applied to a canvas or any other material support in a particular manner. "What the painting is, is exactly what [people] see," he remarked in a relatively early interview.1 With greater emphasis on the "see" than on the "is" of his statement, Ryman later elaborated on his basic thesis:

We have been trained to see painting as "pictures," with storytelling connotations, abstract or literal, in a space usually limited and enclosed by a frame which isolates the image. It has been shown that there are possibilities other than this manner of "seeing" painting. An image could be said to be "real" if it is not an optical reproduction, if it does not symbolize or describe so as to call up a mental picture. This "real" or "absolute" image is only confined by our limited perception.2

Ryman's aesthetic practice is further illuminated by his observation in the late 1960s that "there is never a question of what to paint, but only how to paint. The how of painting has always been the image—the end product."3 For his part he has "wanted to make a painting getting the paint across"—meaning getting paint literally across the surface and, more idiomatically, getting it across as an idea.4

Occupied from the outset with ways of letting paint engage with its surface, Ryman has continuously sought to activate the painted surface, often subtly, while simultaneously approaching the support as if it were the proscenium of a stage. Unlike Untitled (Orange Painting) (1955–59), which he considers his first mature painting, his works typically use white paint, because of its neutrality as a color, and more often than not they are square in format. The exclusion of other hues, and the equalizing of all sides of the support, minimize distraction from the paint as an area warranting the full attention of the viewer.

Untitled (1959) is indicative of his overriding interest in imbuing paint with the power to act on its own behalf. Multidirectional, interwoven, overlapping brushwork and residual globules of paint signify the performance of paint itself, rather than suggesting some quality beyond its own physicality and its behavior in response to the brush. Moreover, the artist's painted signature, the vertically upended "R Ryman," intervenes in the overall activity of the paint. According to Ryman, the signature, "an accepted element of all painting," functions saliently here as a line meant to avert symbolism, and to prevent the painting from being mistaken as "trying to say something."5 Simultaneously a painted sign and an authorial one, the orange-toned signature is engulfed in the all-encompassing field of paint. Close in color to the orange-yellow tint of the work's raw cotton canvas, the signature-as-line-as-physical-paint mediates between the entirety of the painted field and the partially revealed cloth support beneath it.

The paints Ryman has used since the 1950s have varied immensely in viscosity and finish, whether glossy, semiglossy, matte, or dull.6 These many paint qualities, along with the multifarious methods with which Ryman handles them, interact with one another in concert with the material of the painting's support and in view of the painting's scale.

Both Vector (1975/97) and Varese Wall (1975) are large in scale, and both are painted on wood panels. The evenhanded approach to paint application in these works brings up a question: what differentiates the paint of the painting from the paint of the white wall behind it? The two works pose this question somewhat differently by virtue of their respective supports. Vector comprises eleven wood units of the same size, hung equidistant from one another; Varese Wall, on the other hand, appears as one extended surface, propped up from the floor on five small bluish blocks of foam. Measuring eight feet high and twenty-four feet long, the work is braced to stand just over a foot and a half from the wall.7

The wall plays an active role in the experience and meaning of Ryman's works, whatever their size and no matter what the interaction between paint and support. "If you were to see any of my paintings off of the wall, they would not make any sense at all . . . unlike the usual painting where the image is confined within the space of the paint plane," the artist has pointed out.8 In Vector, the empty spaces between the painted panels echo the forms of the panels themselves. Ryman initially painted this work in vinyl acetate, a pigmented commercial glue, at the Kunsthalle Basel for his exhibition there in the summer of 1975. A couple of years later the eleven panels were separated into two artworks, one of five panels (Vector I) and one of six (Vector II), but they were reunited in 1979. In 1997, Ryman painted over the original, vertically brushed vinyl acetate with oil paint, leaving a new, horizontally brushed surface as impassive as the earlier one. In effect, the paint quality of Vector nearly matches that of the wall, from which, however, the panels may be distinguished in that their thin left sides are made of a clear pine wood and their right sides are of redwood. As the light plays on the work's painted surfaces, the panels seem to float ever so slightly away from the wall. In this way the work demonstrates how painted surface, wall, light quality, and overall spatial confines converge to form an image that simultaneously incorporates and contradicts the formerly blank space of a wall.

Varese Wall, like Vector, also exhibits the fine line between a painting and its background wall. Here, in fact, the painting—its title a reference to the walls leading to the villa of Count Panza di Buomo in Varese, Italy—is also a wall of sorts. This painting-cum-wall creates a dialectic with the wall of its given exhibition space, a wall that presumably is painted but is not in any sense a painting. With his introduction of metal fasteners that visibly hold his paintings to their walls, in 1976, Ryman overtly acknowledged the symbiosis between a painting and its supporting wall. Varese Wall furthermore remains ever freshly painted, as does any "real" exhibition wall, since the artist gives it another coat of vinyl acetate whenever it is installed anew.

Vector and Varese Wall anticipate later works of Ryman's in that they verge on obliterating the distinction between the thematic aspect of painting and a painting as a physical object, but never quite do—in fact, this is a distinction they insist upon. These works fully express the idea that the relationship of paint to support, though born of material practicality, is ultimately grounded in the ideational capacity of painting to be about its own activity. Ryman's paintings detail different possibilities for the application of paint. For him, painting remains an ongoing reflection on itself, and in his work it becomes ever more mindful of its differentiation from, yet necessary, attachment to a wall.

Notes

1. Robert Ryman, quoted in Phyllis Tuchman, "An Interview with Robert Ryman," Artforum 9, no. 9 (May 1971), p. 53.

2. Ryman, in Wall Painting (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1979), p. 16.

3. Ryman, in Art in Process, vol. 4 (New York: Finch College Museum of Art/Contemporary Wing, 1969–70), n.p.

4. Ryman, in Tuchman, "An Interview with Robert Ryman," p. 49.

5. Ryman, in Robert Storr, Robert Ryman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, in association with the Tate Gallery, London, 1993), p. 70.

6. For a full explication of Ryman's working methods and materials, see Robert Storr, "Simple Gifts," in ibid., pp. 9–45.

7. I thank Amy Baker Sandback for unpublished information on these paintings from her forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Ryman's work.

8. Ryman, in Gary Garrels, "Interview with Robert Ryman," in Robert Ryman (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 1988), p. 13.

http://www.diacenter.org/exhibs_b/ryman/essay.html

DEGEM: Klangkunst in Deutschland (Sonic Arts in Germany)

CD-ROM, 2000, Wergo T 5150; available from Schott Music & Media, GmbH, Weihergarten 5, 55116 Mainz, Germany; telephone (+49) 6131-246-883/888; fax (+49) 6131-246-252; World Wide Web www.schott-music.com

Reviewed by Oliver Schneller

Paris, France

Klangkunst in Deutschland (Sonic Arts in Germany) is the title of the first CD-ROM presented in both German and English by the German Society for Electroacoustic Music (DEGEM) in collaboration with the Aesthetic Strategies in Multimedia and Digital Networks project of the University of Lüneburg. The disc, issued on the Wergo label, contains portraits and work samples of seven "sound artists" currently living and working in Germany. As a special feature, DEGEM has included its International Documentation of Electroacoustic Music, a gigantic database (in FileMaker and Excel formats) containing a worldwide listing of studios for electronic music and a catalogue of 21,062(!) works written between 1901-1999 by over 4000 composers.

Five individual artists, Werner Cee, Michael Harenberg, Robin Minard, Jutta Ravenna and Johannes S. Sistermanns, as well as the artist-tandem Sabine Schäfer/Joachim Krebs were invited to present themselves and their work with texts, pictures, audio samples, and spoken words. The CD-ROM seems a tremendous medium for the purpose of introducing artists who find themselves working in the zone between music and the visual arts with an emphasis on composed installations and interactive environments. After reading through the informatory texts at his/her own pace, the user has the possibility to get an impression of the spatial set-up of the often rather complex installations by viewing video-clips while listening to the actual acoustic responses. Pure audio files of a higher quality are provided for works where listening is the priority. Needless to say, both audio and video samples in their CD-ROM presentation convey merely an idea of the aura of the works presented. In reality, they may feature 32-channel spatialized sound or highly differentiated light choreography. One artist, Michael Harenberg, aware of this limitation, had the idea to create a new work especially for his contribution to the CD-ROM. His enjoyable "virtual interactive sound installation" PERSIMFANS transforms the graphic user interface into an interactive audio-visual experiential field which invites the user to freely browse through and interact with 15 virtual "rooms" appearing on the monitor. The sounds are also virtual in that they are based on physical modeling of flutes, percussion, and string instruments.

In spite of the fact that each of the contributors were given complete liberty to assemble their presentations according to their own wishes, the disc retains a graceful sense of unity with its engaging user surfaces. In addition, this release provides a vast source of information on the "state-of-Sonic-Arts," with links provided to individual Web sites as well as listings of publications and compact discs. On a technical note: the various plug-ins that are needed to fully activate the HTML- and Java-Script-based applications have been conveniently included on the CD-ROM by DEGEM.

The following provides a brief overview of the individual contributions. Werner Cee (b. 1953), a musical autodidact, fellow of the Akademie Schloß Solitude and Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) in Karlsruhe, and Bourges prize winner in 1993, presents his work in six categories: 1) Sound and Light installations (multi-media); 2) Acoustic Art (composition); 3) Soundscapes (installations); 4) Theater (mostly music theater projects for children); 5) Live-music (improvisations); 6) Ethnomusicological projects, mostly in collaboration with the writer Bettina Obrecht (specializing in music from the Scottish Highlands and Istanbul). His works in these categories range from more or less "traditional" installation set-ups such as microphone/loudspeaker feedback-signals transformed to create a self-generating piece, to the light installations lost (1992) in which a stroboscope is suspended from an elastic cable, to between the lines (1992), coordinating the diffraction of colored light through a mass of glass-splinters with sonic responses, to braindrops (1993), in which the frequency and electronic transformation of the sound of water droplets is controlled by bio-feedback via EEG-processing.

A different aspect of Mr. Cee's work are his "acoustic films," mostly composed for radio production and filed under both of his categories, Acoustic Art (composition) and Soundscapes. While traveling the composer collected recordings of mostly urban environments and later mixed them to create an acoustic portrait. Such an "acoustic film" can then even be performed outdoors, as in the case of Open Air Soundscape (1998), a "piece for summer sunset" lasting over two hours to be performed in a familiar space that is then gradually (acoustically) contextualized and transformed into an Istanbul bazaar or a Cuban village via eight-channel sound diffusion.

Returning to Michael Harenberg (b. 1961), one discovers already in his early works an emphasis on the use of computers. His activities have included collaborations with multimedia artists Clarence Barlow and Barbara Heller, shows at the Documenta in Kassel (1992) and participation in the aforementioned Aesthetic Strategies project at Lüneburg University. Following his early compositions for instrumental ensembles are works in which the sounds of real instruments have been replaced by an array of virtual instruments created by complex physical modeling algorithms. His works Stundenlang Nr.5 for a dancer, four instruments, and virtual flute, E-/L-/M-Medusa for virtual bass flute and computer (1999), and Doublebind (1998), an interactive sound installation for "low-tech" analog equipment and complex computer-controlled physical modeling, make extensive use of this synthesis technique. Inter-music (1996), for Speech Synthesizer, connects to the virtual space of the Internet by reciting all the URLs that were to be found in Mr. Harenberg's browser at the time.

If the accent of Mr. Harenberg's work lies in the creation of the artificial and virtual, the installations of Robin Minard (b.1953, Montreal) seem often to be based on finding links to the organic world through the use of technology. Works such as Silent Music (1995) or Landscape I (1997) consist of hundreds of mushroom-like little piezo loudspeakers that cover the floor or are mounted on walls. The organic analogy of these plant-like configurations that emit soft sounds of computer-controlled MIDI instruments is enhanced by their responsiveness to natural phenomena. In Weather Station (1995), light and climate sensors turn detected weather changes into MIDI control data, while Intermezzo (1999) is a fixture of hundreds of loudspeakers partially hidden among bushes, adding to the acoustic environment of the Federal Garden Show 1999 in Magdeburg, Germany.

The transformation of a given environment through sound is also the theme of Mr. Minard's Neptun (1996) commissioned by the Institute of Electronic Music (IEM) in Graz. Here, two small rooms of a castle in Graz are fortified with a layer of artificial walls behind which lies—invisibly—an 8 cm-thick "loudspeaker ribbon" which circumscribes the two rooms. Water-like, streaming sounds evenly pass through this diffusion field. The composer describes the "loudspeaker ribbon” as:

" A variation of the electrostatic principle sometimes found in high-fidelity loudspeaker systems. The ribbon diffuses sound uniformly across its entire surface. For the installation Neptun a special loudspeaker ribbon, made from a paper-thin amalgam of aluminum and Mylar plastic, was developed and produced together with Christoph Moldrzyk (Berlin)."

Interaction with environments, in particular with hidden or even inaccessible ones, is also one important aspect of the work of Jutta Ravenna (b. 1960). Besides installations using floating sound-buoys to amplify the barely audible sounds of water-insects (LeiseLaute(Feld1), 1994), or the mixing of digital and real cricket-chirping in an abandoned factory hall (LeiseLaute(Feld2), 1994), she has found ways to make the inner world of computer circuit boards acoustically tangible. Through the use of impulse amplification and transposition these sounds become audible to the human ear. By creating sculptures of mounted racks with circuit-boards, often equipped with light- and pressure-sensors, Ms. Ravenna's aim is to "re-materialize and integrate this phenomenon [the circuit board] into the real world in which it is presented."

A particularly original manifestation of this idea is the series of Data-Sound-Windows (Fields 1 to 4) created in 1995. In Field 1, green windows of semi-transparent circuit boards contextualize the sacred space of a church. By placing the construction in front of the church windows the intricate patterns of the circuitry shine through in counterpoint to the usual paintings found on the windows. Field 1 is equipped with light sensors that trace light changes that are transformed into timbral changes in the accompanying soundscape of amplified printer, mouse-click, and ventilator sounds.

By comparison, Cologne artist Johannes S. Sistermanns (b. 1955) stresses the "performance" aspect more than any of the other composers presented on the DEGEM CD-ROM. His work revolves around the idea of resonance in the widest possible sense: "The room becomes a resonance of what is out, the outside is the resonance of what is in."

In Mr. Sistermann's works, "resonance" encompasses the acoustic response of a room or body as well as the resonance of a mind: "I just want to open up a field of infinite possibilities. I make an invitation." Resonance happens in the response of the listener: "Experience yourself as an observer whose body is being played".

To begin with, a practical example of this composer’s idea of resonance can be found in his frequent use of his multi-monochord, which is based on Pythagoras's instrument but which has 39 strings tuned to the same pitch. His Lichtung (1997) suspends three such instruments in the atrium of the SFB-Soundgallery in Berlin. Their excitation occurs via membrane-contact by transferring radio and television sounds onto the bodies of the monochords.

In his “TV-under-water-performance," Water under Water (1997), the monochord at first resonates to the sounds of Mr. Sistermann's voice and is then struck by pebbles collected in his mouth during a dive in the Rhine river.

A broader idea of resonance comes to carry the pieces Paris, drinnen (1992) and Klangort (1992). The former is a radiophonic sound-project for interior spaces (passages, metro stations, malls, and private apartments) found in Paris. These spaces maintain contact with the outside world through various openings, windows, and doors. Mr. Sistermann found the particular resonance tone of each room and recorded himself humming it. The results of this process including additional noises recorded in and around these spaces were then played into a piano with the sustain pedal down and re-recorded with the added level of resonance. Klangort for 24 a cappella singers in 24 private apartment spaces with open windows presents a live application of a similar idea. All 24 singers chant the resonance tones of their rooms at the same time out of their open windows, thus giving a city block a magical acoustic ambience.

The most elaborate presentation of a single work on this CD-ROM is the project sonic lines n'rooms by Joachim Krebs and Sabine Schäfer, who have worked together as a team since 1995. A commission by the SüdWestRundfunk (SWR), the piece was presented at the Donaueschinger Musiktage in October 1999 in the basement of the old library building, the Hofbibliothek. The 32-channel spatial sound composition spreads out through four connected rooms, which together become a "traversable four-limbed spatial sound body." Each of the four rooms contain eight loudspeakers set up in different configurations—diagonal, elliptical, and trapezoidal—each with their own diffusion patterns of varying sound sources. The CD-ROM features detailed plans of the set-up (so-called "consistency-maps") as well as the spatial trajectories of the source sounds and their transformations, along with photos, video clips, and audio samples.

The objective of the installation was to intensify the experience of acoustic conditions through the artistic-poetic manipulation of architectural space. The sounds themselves fluctuate between low continuous drones and rhythmic and discrete artificial or processed animal utterances. Controlling this elaborate sound-space composition is the Topoph40D, a spatialization system developed for Sabine Schäfer by Sukandar Kartadinata during the early 1990s. Three computers share the control of this system together with a special mixing board built to fit this configuration. Computer A receives the itineraries of the desired spatial motions as MIDI data from a sequencer, transforms them into system-exclusive control data that is relayed to computers B and C which then translate the data into the format used by the mixer which in turn passes out the discrete signals to the speakers by means of voltage controlled amplification (VCA).

Other projects involving elaborate spatialization are Sabine Schäfer's TopophonicPlateaus (1995), for 27-channel sound, electroacoustic sounds, human voices, and computer-controlled piano, SonicRooms (from 1997), a group of sound-tents with individual multi-channel spatialization, and Joachim Krebs's AquaAngelusVox (1998), a 16-channel sound installation with visual projections premiered in the Zeiss-planetarium in Berlin.

Be it through the statements of the artists, through the audio or video samples of their works, or through score excerpts and diagrams, this CD-ROM presents a wealth of stimulation and ideas around the context of "Sonic Art," "Audio/Visual Art,” "Sound ART," and “SOUND Art," or whatever definition one chooses to settle with. In spite of the practical necessity to be selective, the expectation raised by the title to present an overview of "Sonic Arts in Germany" is not disappointed, and one leaves one's screen with an inspired air and the hope that listening/seeing/perceiving will continue to be challenged through the creation of art.

http://mitpress2.mit.edu/e-journals/Computer-Music-Journal/reviews/26-1/schneller-germanycdr.html

DEGEM: Klangkunst in Deutschland (Sonic Arts in Germany)

CD-ROM, 2000, Wergo T 5150; available from Schott Music & Media, GmbH, Weihergarten 5, 55116 Mainz, Germany; telephone (+49) 6131-246-883/888; fax (+49) 6131-246-252; World Wide Web www.schott-music.com

Reviewed by Oliver Schneller

Paris, France

Klangkunst in Deutschland (Sonic Arts in Germany) is the title of the first CD-ROM presented in both German and English by the German Society for Electroacoustic Music (DEGEM) in collaboration with the Aesthetic Strategies in Multimedia and Digital Networks project of the University of Lüneburg. The disc, issued on the Wergo label, contains portraits and work samples of seven "sound artists" currently living and working in Germany. As a special feature, DEGEM has included its International Documentation of Electroacoustic Music, a gigantic database (in FileMaker and Excel formats) containing a worldwide listing of studios for electronic music and a catalogue of 21,062(!) works written between 1901-1999 by over 4000 composers.

Five individual artists, Werner Cee, Michael Harenberg, Robin Minard, Jutta Ravenna and Johannes S. Sistermanns, as well as the artist-tandem Sabine Schäfer/Joachim Krebs were invited to present themselves and their work with texts, pictures, audio samples, and spoken words. The CD-ROM seems a tremendous medium for the purpose of introducing artists who find themselves working in the zone between music and the visual arts with an emphasis on composed installations and interactive environments. After reading through the informatory texts at his/her own pace, the user has the possibility to get an impression of the spatial set-up of the often rather complex installations by viewing video-clips while listening to the actual acoustic responses. Pure audio files of a higher quality are provided for works where listening is the priority. Needless to say, both audio and video samples in their CD-ROM presentation convey merely an idea of the aura of the works presented. In reality, they may feature 32-channel spatialized sound or highly differentiated light choreography. One artist, Michael Harenberg, aware of this limitation, had the idea to create a new work especially for his contribution to the CD-ROM. His enjoyable "virtual interactive sound installation" PERSIMFANS transforms the graphic user interface into an interactive audio-visual experiential field which invites the user to freely browse through and interact with 15 virtual "rooms" appearing on the monitor. The sounds are also virtual in that they are based on physical modeling of flutes, percussion, and string instruments.

In spite of the fact that each of the contributors were given complete liberty to assemble their presentations according to their own wishes, the disc retains a graceful sense of unity with its engaging user surfaces. In addition, this release provides a vast source of information on the "state-of-Sonic-Arts," with links provided to individual Web sites as well as listings of publications and compact discs. On a technical note: the various plug-ins that are needed to fully activate the HTML- and Java-Script-based applications have been conveniently included on the CD-ROM by DEGEM.

The following provides a brief overview of the individual contributions. Werner Cee (b. 1953), a musical autodidact, fellow of the Akademie Schloß Solitude and Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) in Karlsruhe, and Bourges prize winner in 1993, presents his work in six categories: 1) Sound and Light installations (multi-media); 2) Acoustic Art (composition); 3) Soundscapes (installations); 4) Theater (mostly music theater projects for children); 5) Live-music (improvisations); 6) Ethnomusicological projects, mostly in collaboration with the writer Bettina Obrecht (specializing in music from the Scottish Highlands and Istanbul). His works in these categories range from more or less "traditional" installation set-ups such as microphone/loudspeaker feedback-signals transformed to create a self-generating piece, to the light installations lost (1992) in which a stroboscope is suspended from an elastic cable, to between the lines (1992), coordinating the diffraction of colored light through a mass of glass-splinters with sonic responses, to braindrops (1993), in which the frequency and electronic transformation of the sound of water droplets is controlled by bio-feedback via EEG-processing.

A different aspect of Mr. Cee's work are his "acoustic films," mostly composed for radio production and filed under both of his categories, Acoustic Art (composition) and Soundscapes. While traveling the composer collected recordings of mostly urban environments and later mixed them to create an acoustic portrait. Such an "acoustic film" can then even be performed outdoors, as in the case of Open Air Soundscape (1998), a "piece for summer sunset" lasting over two hours to be performed in a familiar space that is then gradually (acoustically) contextualized and transformed into an Istanbul bazaar or a Cuban village via eight-channel sound diffusion.

Returning to Michael Harenberg (b. 1961), one discovers already in his early works an emphasis on the use of computers. His activities have included collaborations with multimedia artists Clarence Barlow and Barbara Heller, shows at the Documenta in Kassel (1992) and participation in the aforementioned Aesthetic Strategies project at Lüneburg University. Following his early compositions for instrumental ensembles are works in which the sounds of real instruments have been replaced by an array of virtual instruments created by complex physical modeling algorithms. His works Stundenlang Nr.5 for a dancer, four instruments, and virtual flute, E-/L-/M-Medusa for virtual bass flute and computer (1999), and Doublebind (1998), an interactive sound installation for "low-tech" analog equipment and complex computer-controlled physical modeling, make extensive use of this synthesis technique. Inter-music (1996), for Speech Synthesizer, connects to the virtual space of the Internet by reciting all the URLs that were to be found in Mr. Harenberg's browser at the time.

If the accent of Mr. Harenberg's work lies in the creation of the artificial and virtual, the installations of Robin Minard (b.1953, Montreal) seem often to be based on finding links to the organic world through the use of technology. Works such as Silent Music (1995) or Landscape I (1997) consist of hundreds of mushroom-like little piezo loudspeakers that cover the floor or are mounted on walls. The organic analogy of these plant-like configurations that emit soft sounds of computer-controlled MIDI instruments is enhanced by their responsiveness to natural phenomena. In Weather Station (1995), light and climate sensors turn detected weather changes into MIDI control data, while Intermezzo (1999) is a fixture of hundreds of loudspeakers partially hidden among bushes, adding to the acoustic environment of the Federal Garden Show 1999 in Magdeburg, Germany.

The transformation of a given environment through sound is also the theme of Mr. Minard's Neptun (1996) commissioned by the Institute of Electronic Music (IEM) in Graz. Here, two small rooms of a castle in Graz are fortified with a layer of artificial walls behind which lies—invisibly—an 8 cm-thick "loudspeaker ribbon" which circumscribes the two rooms. Water-like, streaming sounds evenly pass through this diffusion field. The composer describes the "loudspeaker ribbon” as:

" A variation of the electrostatic principle sometimes found in high-fidelity loudspeaker systems. The ribbon diffuses sound uniformly across its entire surface. For the installation Neptun a special loudspeaker ribbon, made from a paper-thin amalgam of aluminum and Mylar plastic, was developed and produced together with Christoph Moldrzyk (Berlin)."

Interaction with environments, in particular with hidden or even inaccessible ones, is also one important aspect of the work of Jutta Ravenna (b. 1960). Besides installations using floating sound-buoys to amplify the barely audible sounds of water-insects (LeiseLaute(Feld1), 1994), or the mixing of digital and real cricket-chirping in an abandoned factory hall (LeiseLaute(Feld2), 1994), she has found ways to make the inner world of computer circuit boards acoustically tangible. Through the use of impulse amplification and transposition these sounds become audible to the human ear. By creating sculptures of mounted racks with circuit-boards, often equipped with light- and pressure-sensors, Ms. Ravenna's aim is to "re-materialize and integrate this phenomenon [the circuit board] into the real world in which it is presented."

A particularly original manifestation of this idea is the series of Data-Sound-Windows (Fields 1 to 4) created in 1995. In Field 1, green windows of semi-transparent circuit boards contextualize the sacred space of a church. By placing the construction in front of the church windows the intricate patterns of the circuitry shine through in counterpoint to the usual paintings found on the windows. Field 1 is equipped with light sensors that trace light changes that are transformed into timbral changes in the accompanying soundscape of amplified printer, mouse-click, and ventilator sounds.

By comparison, Cologne artist Johannes S. Sistermanns (b. 1955) stresses the "performance" aspect more than any of the other composers presented on the DEGEM CD-ROM. His work revolves around the idea of resonance in the widest possible sense: "The room becomes a resonance of what is out, the outside is the resonance of what is in."

In Mr. Sistermann's works, "resonance" encompasses the acoustic response of a room or body as well as the resonance of a mind: "I just want to open up a field of infinite possibilities. I make an invitation." Resonance happens in the response of the listener: "Experience yourself as an observer whose body is being played".

To begin with, a practical example of this composer’s idea of resonance can be found in his frequent use of his multi-monochord, which is based on Pythagoras's instrument but which has 39 strings tuned to the same pitch. His Lichtung (1997) suspends three such instruments in the atrium of the SFB-Soundgallery in Berlin. Their excitation occurs via membrane-contact by transferring radio and television sounds onto the bodies of the monochords.

In his “TV-under-water-performance," Water under Water (1997), the monochord at first resonates to the sounds of Mr. Sistermann's voice and is then struck by pebbles collected in his mouth during a dive in the Rhine river.

A broader idea of resonance comes to carry the pieces Paris, drinnen (1992) and Klangort (1992). The former is a radiophonic sound-project for interior spaces (passages, metro stations, malls, and private apartments) found in Paris. These spaces maintain contact with the outside world through various openings, windows, and doors. Mr. Sistermann found the particular resonance tone of each room and recorded himself humming it. The results of this process including additional noises recorded in and around these spaces were then played into a piano with the sustain pedal down and re-recorded with the added level of resonance. Klangort for 24 a cappella singers in 24 private apartment spaces with open windows presents a live application of a similar idea. All 24 singers chant the resonance tones of their rooms at the same time out of their open windows, thus giving a city block a magical acoustic ambience.

The most elaborate presentation of a single work on this CD-ROM is the project sonic lines n'rooms by Joachim Krebs and Sabine Schäfer, who have worked together as a team since 1995. A commission by the SüdWestRundfunk (SWR), the piece was presented at the Donaueschinger Musiktage in October 1999 in the basement of the old library building, the Hofbibliothek. The 32-channel spatial sound composition spreads out through four connected rooms, which together become a "traversable four-limbed spatial sound body." Each of the four rooms contain eight loudspeakers set up in different configurations—diagonal, elliptical, and trapezoidal—each with their own diffusion patterns of varying sound sources. The CD-ROM features detailed plans of the set-up (so-called "consistency-maps") as well as the spatial trajectories of the source sounds and their transformations, along with photos, video clips, and audio samples.

The objective of the installation was to intensify the experience of acoustic conditions through the artistic-poetic manipulation of architectural space. The sounds themselves fluctuate between low continuous drones and rhythmic and discrete artificial or processed animal utterances. Controlling this elaborate sound-space composition is the Topoph40D, a spatialization system developed for Sabine Schäfer by Sukandar Kartadinata during the early 1990s. Three computers share the control of this system together with a special mixing board built to fit this configuration. Computer A receives the itineraries of the desired spatial motions as MIDI data from a sequencer, transforms them into system-exclusive control data that is relayed to computers B and C which then translate the data into the format used by the mixer which in turn passes out the discrete signals to the speakers by means of voltage controlled amplification (VCA).

Other projects involving elaborate spatialization are Sabine Schäfer's TopophonicPlateaus (1995), for 27-channel sound, electroacoustic sounds, human voices, and computer-controlled piano, SonicRooms (from 1997), a group of sound-tents with individual multi-channel spatialization, and Joachim Krebs's AquaAngelusVox (1998), a 16-channel sound installation with visual projections premiered in the Zeiss-planetarium in Berlin.

Be it through the statements of the artists, through the audio or video samples of their works, or through score excerpts and diagrams, this CD-ROM presents a wealth of stimulation and ideas around the context of "Sonic Art," "Audio/Visual Art,” "Sound ART," and “SOUND Art," or whatever definition one chooses to settle with. In spite of the practical necessity to be selective, the expectation raised by the title to present an overview of "Sonic Arts in Germany" is not disappointed, and one leaves one's screen with an inspired air and the hope that listening/seeing/perceiving will continue to be challenged through the creation of art.

http://mitpress2.mit.edu/e-journals/Computer-Music-Journal/reviews/26-1/schneller-germanycdr.html

Robert Ryman·reduction and emotion

A white monochrome is often assumed to belong to a tendency in modernism that, through a process of elimination, strives to reveal the essential characteristics of a medium in order to arrive at a notion of that mediumËs "pure form;" or it is thought to represent what remains after painting has refined itself almost to the point of nonexistence, becoming the embodiment of an idea about art. In his work, Robert Ryman pursues neither purity nor minimal paintingËs logical extreme. Rather, he reduces visual information and reference in order to isolate and examine the fundamental physical attributes of painting. In the process, he foregrounds, and makes pictorial, elements not usually considered intrinsic to the visual experience of art: the artistËs signature, the workËs title, its support, its hanging devices, even its interaction with the space around it.

Ryman limits his palette to white because it is recessive enough to allow paintingËs other physical properties a voice and it makes his exploration of paint and paint handling more evident than darker, brighter colors or multi-hued compositions would. He also uses white to examine the very nature of color. Usually equated with the blank canvas and read as absence, in RymanËs hands white is endlessly varied and very much present. It is smooth and slick; soft and subtle; dry and chalky; cool like cream cheese or warm like heavy cream. In works from the late fifties and early sixties, colorful underpainting and printed matter are visible beneath the surfaces. Later, supports made of different metals or fiberglass and hanging devices in plastic, metal, tape, or wood lend subtle color to the paintings. At different points, RymanËs signature appears in ocher paint or graphite. The large Surface veils of 1970“71 have blue chalk borders. In fact, the percentage of true monochromes in RymanËs oeuvre is not great. Most of his works are "almost monochromes."

In 1971, one review identified Ryman as "the last functional member of the third generation of Abstract Expressionism"1 while another claimed that his works seemed "to make more sense of the idea of [seriality] than almost anyone elseËs do."2 These appraisals situate RymanËs project between two generations of U.S. artists. First and foremost, he is a painter who owes a debt to the New York school. However, he is also a member of the generation of conceptualists and postminimalists with which he emerged. Like them, he creates within the limitations of a specific, preestablished set of guidelines that emphasizes the process of art-making, often using the strategies of modularity and repetition.

Ryman is unique in reconciling a profound commitment to painting with systemic procedures commonly associated with minimal and conceptual art. Always analytical, by his own admission, he is also romantic and, in this, he aligns himself with Mark Rothko: "RothkoËs work might have a similarity with mine in the sense they may both be kind of romantic [. . .] I mean in the sense that Rothko is not a mathematician, his work has very much to do with feeling, with sensitivity."3 As with RothkoËs pared-down canvases, meaning lies in the sheer beauty of RymanËs deeply sensual white paintings. They are simultaneously emotive and reductive.

1. Willis Domingo, "Robert Ryman," Arts magazine (March 1971), p.17. Quoted in Lynn Zelevansky, "Chronology," Robert Ryman,

London: Tate Gallery, 1993, p.217“18.

2. Kenneth Baker, "Ryman at Fischbach," Artforum (April 1971), p.79. Quote from Zelevansky, p.218.

3. Quoted in Robert Storr, "Simple gifts," Robert Ryman, London: Tate Gallery, 1993, p.39.

http://www1.uol.com.br/bienal/24bienal/nuh/inuhmonryma02a.htm

In Touch with Vision

In Touch with Vision

John Haber

in New York City

Gallery-Going, Winter 2005:

Richard Tsao, Petah Coyne, and Robert Ryman

Actually, my own hope is that a less qualified acceptance of the importance of sheerly abstract or formal factors in pictorial art will open the way to a clearer understand of the value of illustration as such—a value which I, too, am convinced is indisputable.

— Clement Greenberg

Tired of theories of abstract art? You know, all that critical agonizing over formalism and mere illusion, the linear and the painterly, or the death of Modernism and the death of irony. Let me offer yet one more suitably magisterial opposition—between the visionary and the sensual, the transcendental and the tactile, space and earth, or maybe just geometry and goo.

Seeing in the material world

Try the game for yourself. It may not prove anything, but it can be fun.

Surely the immaterial includes Abstract Expressionism, with all that talk of pure painting, an arena for action, and "the sublime is now." So what if I must set aside Mark Rothko's love of Giotto and his belief in pictorial space as akin to Renaissance architecture? It might include, too, the open fields of color—or, at times, the very absence of color—in Hilla Rebay, Agnes Martin, Joe Baer, and Ellsworth Kelly. Never mind the association of geometric abstraction with painting as object. It surely has to include Op Arts like Julian Stanczak, even if you feel the dizziness in your stomach before it reaches your eyes.

As for the stuff that gets on your hands, try another token of Abstract Expressionism, the drip painting. Try earthworks, Ana Mendieta's bodily fluids, and Lee Bontecou's metal teeth and soot. Compare the elaborate supports for plain white from Robert Ryman on through James Hyde and Leonardo Drew. Take in the imaginary oceans of Pat Steir, Vija Celmins, and later Joseph Stashkevetch or, with Kelley Walker, actual chocolate syrup.

So what if each artist creates memorable illusions? So what if they have elicited enough conceptual arguments to choke a thesis advisor? Even Peter Halley, the arch theorist of geometry as Michel Foucault's prison cells, gave abstraction the rubbery bumps of Rolotex.

I say all that because painting survives on variety and contradiction, beyond the familiar passions over soft brushes and hard edges. I say it because, at least since Cubism, contradictions like these change one's understanding of art and perception. They make illusion a matter not just of art-school technique or the psychology of vision, but of living in the material world. In turn, they make the very physical being of art part of the active imagination. Cubism reduced space and sensation not to planes or cubes, but to a greater variety of cues for the imagination, from textures to song titles—the deliberate incongruity, challenging the coherence of any imaginative vision, that Foucault called a heterotopia. By habits of belief, one may think of vision as immaterial, something apart from how people first find their way around the world, but, in art as in life, that may be as much an idealization as single-point perspective.

I say it, too, because few shows have had me feeling vision in my gut like the latest from Richard Tsao and Petah Coyne. Tsao makes pigment into a layer that outstrips its canvas support but picks up light from deep within. Coyne starts with the stickiness of earth and tar, but with an imagery as thick as a Victorian novel. If all that sounds too strange, imagine first what happens when Ryman himself reintroduces brushwork, colored paint, and bare canvas. It shows how many of the same contradictions have been lurking all along in some of art's apparently quietest visions.

Less than white

Robert Ryman's evolution is so intimately tied up with the acme of formalism that the evident brushwork of a previous show could easily have seemed a mistake. Perhaps, one was tempted to think, he was trying too hard. Perhaps older artists safely entering the pantheon feel they just have to have broader strokes, more open spaces, and cleaner, brighter colors, like a late modern version of Rembrandt's blur. Think of like Willem de Kooning in his sometimes exhausted, sometimes rapturous 1980s. Perhaps next time Chuck Close, who already over the years has adopted first overt gesture and now daguerreotypes, will continue his march backward through the centuries and start pouncing his traces into fresco.

Ryman's latest show grows still more gestural, but also murkier. It adds literal color to his trademark white paint, bare metal bolts, and white walls. The strokes assume a character of their own, but one focuses on the areas of color and bare canvas more than on the artist's air of control. One sees painting again, apart from its hanging. And once again, as so often in Ryman's career, one has to question what it means to speak of white on white.

Ryman's monochrome sounds austere without even the spiritual comforts of asceticism. He shuns the existential drama of large scale, intense color, or for that matter black on black, as in Ad Reinhardt or late Rothko. Besides, both Reinhardt and Rothko cared deeply shades of gray, with black itself an illusion waiting to give way to experience. Ryman relishes how much he can do with one can of paint, a surface and its supports, the sheetrock walls behind them, and the industrial associations of all these. Like Minimalism, his art does not simply announce its integrity in the present. Rather, it arises from chance encounters—in the gallery with the viewer, during its installation before that, or earlier still, during its making.

With Kelly, for one, that can mean work that mimics the fall of color and shadow onto wood and canvas. Ryman's sense of the art object can appear more minimal or funkier. Either way, however, it allows a more down-to-earth appreciation. One may have fewer illusions, but one still has the actual apparitions within the work. Call it Pomo's concentration on the gallery as institution, but without the critical displeasure.

Ryman took up white just before 1960, with rather sloppy strokes, sometimes signing the work in white for good measure. Before long he was covering the panel and effacing individual strokes—but hardly hiding them. The wall brackets became part of the game, literally without a screw loose, as obvious in the mini-retrospective of his room at Dia:Beacon. Color appeared, but because it arose from the encounter of material objects with gallery light and cast shadow. The artist hardly needed a color chart to know that there is no such thing as simply white and that a great colorist need not even attempt to control his colors. Who needs nuance when one can have all that?

Does his dabbling with brushwork and color now mark a retreat, a career run out of its own logic? Perhaps his art has come to reflect on its own shadows. Perhaps Ryman has merely dispersed them into yet another chance encounter still to come. Or perhaps he has obliterated the boundaries between the visual and the material so thoroughly as to find a space empty even of white. And now at least two younger artists are ready to fill it.

Moon river

For one extended moment, Richard Tsao took me completely into the space of vision. His modest canvases leave ample space for an exhibition's white walls. A still more intense white surrounds each work. That glow comes from using the gallery fixtures as broad spotlights, but it seems to arise from the work itself. If Ryman enables white paint to cast colored shadows, Tsao uses concentrated color to fill a room with points of light.

Eventually, I had to break that moment and get closer, if only to see how he does it. The water-based medium contains fabric pigment and marble dust. He could tell you what else, but he would have to kill you first. The highly reflective components give even pale tones the depth of pure primary colors. As he pours paint, without a brush, the colors may blend, bleed into one another, or add to each other's intensity. Sometimes the cracks take on the fine detail of deliberate drawing. As with Morris Louis's darker poured paintings, the components visible along the sides come as a surprise and serve as part of the image, too.

They also call attention to its material support, and up close one perceives the paint as a series of thin layers on equal footing with canvas. The ground media give the layers considerable strength, even when they stick out irregularly from the edges. Occasionally Tsao peels off a chip as it dries and transplants it elsewhere. Like much of the color, those thin patches may make one think of flower petals as much as marble chips, and that labor over a painting's ground may have something in common with tending soil. The catalog essay, by Benjamin Genocchio, suggests a connection to the flower markets of the artist's childhood in Thailand.

The rough edges also make the canvases appear like fragments torn from something more continuous. The images, too, evoke a larger scale in space and time. They may recall river beds and lunar or planetary surfaces, and Tsao is fond of titles like Flood and Sci-Fi. No question such associations make poured paint comfortingly familiar, attractive, and self-referential. Color-field painting has a history, after all.

However, the associations have something else in common, too, however. They all exist in a space neither fully organic nor inorganic, like abstraction finding its way between the human image and material object. They suggest not just poured media and flowing color, but the marks of processes long past. They allow one again to see paint as both itself and trace, substance and image.

They help keep the work from coming off as a little too pretty, a little too neat, or a little too close to camp, like paintings of artificial flowers or retreads of Jules Olitski crossed with Ross Bleckner. I take comfort in knowing that work in progress normally lies heavily all over Tsao's Brooklyn studio rather than on white walls, and he has had to negotiate with his landlord to keep the liquids from turning the place into another uninhabited world. I imagine it as yet a greater mutual saturation of the tactile and visual.

Dress rehearsal

Petah Coyne, too, believes in getting her hands dirty, and she makes me feel that I may never shake the dirt from my skin as well. She drew attention in the late 1980s for constructions of soil held together by goodness knows what, but definitely not by goodness. They look earthy, rough, dense, rich, and strange.

Perhaps they look at times a little too rich. I often forget to look beyond their palpability and estheticism. They avoid formalism on one side or obvious representation on the other. They sit comfortably in a gallery, where earthworks would spill over its edges or simple statuary would declare a public place.

They do, however, implicate art and artist alike in that rough interior space, with a notion of femininity as unsettling as Bontecou's soot and ashes. Soil may suggest nurturing, like the space of Tsao's imagined flowers. It may suggest humility in the face of forces beyond one's control, like that of Candide cultivating his garden. This soil, however, has no space for penetration or time for rest. Besides, it gets in the way of good housekeeping. It would leave dark stains on a wedding dress.

In the last decade, Coyne has in fact let those stains appear, and the work has become that much more interesting in the process. It is still earthy, dense, rough, and strange, but it spills over the sculptural, and it cherishes associations. Some works resemble dresses, veils, or female busts, hardened in pitch black or pure white.

Coyne has not transcended color but imperfectly effaced it. Up close, a torso spreads into birds. Seedpods morph into tresses of hair. Roses and lace vie with their covering of with paint and tar. They make feminine imagery more explicit than in her earlier work, but with a terrifying melancholy. At her gallery, one could be the witness to a broken wedding, an altar left without a bride.

At SculptureCenter, a small selection from throughout her career has the main floor—appropriately enough, above the crawl spaces of the crenellated basement used for group shows. Coyne's blackened roses rise from Maya Lin's converted factory floor. Earth clings to the walls and, as the retrospective's title has it, "Above and Beneath the Skin." The lace and birds hang from the high, half-open industrial ceiling, on long cords that blend into the suspended surfaces, images, masses, and materials. I thought of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, always in her wedding dress, floating once more in the dark, empty rafters of Pip's imagination.

http://www.haberarts.com/geogoo.htm

Robert Ryman: New Paintings

Art Review — NewYorkArtWorld ®

White is the color of death in Japan. Maybe other places too. In most parts of the world, though, it is the color of birth, life, regeneration, etc. Whatever else, white is foremost (not human skin color, because there are no white people--or black, red, or yellow); it transcends other colors, all of which signify something more specific. White is more universal, and black is too; both also signify nothing, blankness. There is no neutrality in any of this.

Robert Ryman doesn't start with white, but it is the field in which he finally works. And, in fact, it's not necessarily pure white, but maybe a little off, and certainly affected by the colors under it and the shadows cast by raised brushstrokes. In that sense Ryman's use is opposite of traditional method, which would have white as a primer or an undercoat that brings light to the colors on top of it. In Ryman, illumination supercedes darkness.

The paintings are literally paintings--paint applied to surfaces. There are no images, as in Jasper Johns, whose work they most resemble in their considered brushwork. Nor are there implied universes of space, as in Rothko or Newman, or manipulations of the framing, as in Frank Stella. In other words, no illusions, or allusions, or at least the illusion of no illusions. Any one of these rectangles is simply a painting, as a tree, for instance, is simply a tree. Its substance is a stretch of fabric, darker (linen) or lighter (canvas), made dependably of tightly woven vertical and horizontal threads. In all the paintings the fabric is left bare, unpainted, around the outer edges, so there is no doubt about its presence, its existential importance. Then first is put down an underlying darker layer of paint--green, yellow, red, salmon, black, light green, mustard, wine--then on top of that a layer of white. Always the darker layer shows, around the edges and/or in glimpses through the white.

There is a kind of exquisite responsibility involved, because the fabric is like a microcosmic substructure, an almost infinitesimal grid on which the brushstrokes play out, something like notes on a staff of music, or rather like music itself. The white is not covering the darker color, which in turn is not covering the fabric. Rather, each grows out of the other, plays with the other, like jazz, or music in general. Looking at a surface, one becomes totally immersed in its composition, its interplay of gestures, improvisations that ultimately come from the grid, emerging through the darker layer to the white. The gestures are the flowering of the grid, in as many ways as the hand moves to the mind and the emotions, and the motor responses of human experience.

What matters is that everything takes place up close, within the immeasurable thickness of the painting itself, where the painter is. The whole settles within the vision from a distance, but ultimately it is not the ethereality of the paintings that is impressive. It is their physicality, their insistence on being. Each is named with a single word, usually as a noun, occasionally and interestingly as a verb that might be taken as a noun. They are to be explored, and to be accepted in their totality and imperfections, like a tree.

The paintings, all from 2001 and 2002, were exhibited from October 11 through November 9, 2002, at PaceWildenstein, 534 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10001. Phone 212 421 3292. Fax 212 421 0835. pacewildenstein.com.

http://www.newyorkartworld.com/reviews/ryman.html

Monday, May 15, 2006

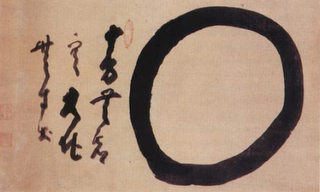

enso

The enso, a simple circle drawn with a single, broad brushstroke, is the zen symbol of infinity. It represents the infinite void, the 'no-thing,' the perfect meditative state, and Satori (enlightenment.)

http://altreligion.about.com/library/glossary/symbols/bldefsenso.htm

The enso is one of the deepest symbols in Japanese zen: a symbolic representation of enlightenment, encompassing the universe in an endless, cyclical line. For the practitioner, the act of creating each single circle is a visual ko-an in which the state of that moment is revealed. As a daily practice, drawing Zen circles can act as a spiritual diary. No deception is possible in painting an enso, for the character of the artist is fully exposed in its nakedness. The more one contemplates it, the more profound its simplicity becomes...

http://wwwnew.towson.edu/theatremfa/artists/ensopage.html

The Zen symbol "supreme" is an enso, a circle of enlightenment. The Shinjinmei, written in the sixth century, refers to the Great Way of Zen as "A circle like vast space, lacking nothing, and nothing in excess," and this statement is often used as an inscription on enso paintings. The earliest reference to a written enso, the first Zen painting, occurs in the Keitokudento-roku, composed in the eighth century:

A monk asked Master Isan for a gatha expressing enlightenment. Isan refused saying, "It is right in front of your face, why should I express it in brush and ink?"

The monk then asked Kyozan, another master, for something concrete. Kyozan drew a circle on a piece of paper, and said, "Thinking about this is and then understanding it is second best; not thinking about it and understanding it is third best." (He did not say what is first best.)

Thereafter Zen circles became a central theme of Zen art. Enso range in shape from perfectly symmetrical to completely lopsided and in brushstroke (sometimes two brushstrokes) from thin and delicate to thick and massive. Most paintings have an accompanying inscription that gives the viewer a "hint" regarding the ultimate meaning of a particular Zen circle. The primary types of enso are: (1) Mirror enso: a simple circle, free of an accompanying inscription, leaving everything to the insight of the viewer. (2) Universe enso: a circle that represents the cosmos (modern physics also postulates curved space). (3) Moon enso: the full moon, clear and bright, silently illuminating all beings without discrimination, symbolizes Buddhist enlightenment. (4) Zero enso: in addition to being curved, time and space are "empty," yet they give birth to the fullness of existence. (5) Wheel enso: everything is subject to change, all life revolves in circles. (6)Sweet cake enso: Zen circles are profound but they are not abstract, and when enlightenment and the acts of daily life-"sipping tea and eating rice cakes"-are one, there is true Buddhism. (7) "What is this?" enso: the most frequently used inscription on Zen circle paintings, this is a pithy way of saying, "Don't let others fill your head with theories about Zen; discover the meaning for yourself!"

http://zenart.shambhala.com/browse-gallery.htm?selectedBrowseKey=2488

The Enso (Japanese for 'circle') is a Zen symbol of the absolute, the true nature of existence and enlightenment. It is a symbol that combines the visible and the hidden, the simple and the profound, the empty and the full. As an expression of infinity, it has links to the western lemniscate, and may be painted so that there is a slight opening somewhere in the circle, showing that the Enso is not contained in itself, but that it opens out to infinity. In Zen art, the space on the page is at least as important as the brushstrokes themselves. It is no coincidence that the feeling of satori, a state of spiritual enlightenment beyond the plane of discrimination and differentiation, is often described as that of infinite space.

The Enso is a popular subject in Zen painting, where the circle is drawn in a single brushstroke and the state of mind of the painter is said to be indicated by the resulting circle - a strong and balanced Enso can only be painted by someone who is in equilibrium and inwardly calm. The very imperfections and contours of the Enso, which must be painted by the human hand rather than constructed as a mathematically correct circle, make the Enso a manifestation of perfection - it is perfect just as it is.

http://www.byzant.com/symbols/enso.asp

An enso ('circle') is the symbol of Zen itself and so an important art subject. fig. 17 is by an influential monk named Inzan (1758-1817), a 'grand-disciple' of Hakuin who trained many teachers. All of Hakuin Rinzai Zen (there are other schools) today comes through either Inzan or Takuju.

The circle itself represents the material world with its endless cycles. The space in the middle represents the emptiness at the heart of Zen.

This enso was brushed in two strokes, though one is usual. Inzan was probably trying to show directly the duality of good and evil, male and female...that together make up the whole of our world.

Zen art is the only religious art that I know with a sense of humor and delight.

http://www.zenpaintings.com/collecting-new.htm

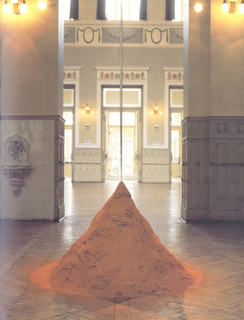

Richard Long: The Time of Space

Haunch of Venison, London

3 January-10 February 2006

Since 1967, Richard Long has used walking as the basis of his artistic practice. What appears in the gallery may be a sculpture constructed from natural materials, a photograph of a sculpture made in situ, or a text, but none of these would be possible without the artist's walks: the experience of time and motion in the landscape finding its mode of expression and memorial.

His most recent exhibition, at the Haunch of Venison gallery in London, is spread over three floors. The first floor displays three photos taken during the course of a 15-day walk in the semi-desert Karoo region of South Africa. 'Flash Flood' proclaims its title over a dark foreground of scrub, while storm clouds sweep dramatically across the ridges - almost a title still from a film. The other two photographs document sculptures Long has created: in 'Karoo Crossing', by scuffing into definition and bordering with stones two meandering and intersecting paths, and in 'Stones and Stars' by setting stones on end on a hillside. Both sculptures seem to have a greater affinity with naturally occurring shapes than with ancient earthworks: the crossing is reminiscent of a microscopic image of a chromosome, while the vertical stones resemble a small colony of cacti growing among other desert plants.

Just before the stairs is the first text piece in the exhibition, 'Walking Music'. This details, in green and orange lettering, six songs, 'In mind each day', as Long walked for six days through Ireland, 'from the Blackwater River to the Burren to the Athenry'. The songs range from the traditional air, 'Roisin Dubh', to Johnny Cash's 'I Still Miss Someone', via the Beatles' cover of 'Rock and Roll Music'. The titles and musicians' details are mysterious, leaving the viewer to guess whether Long tuned in to some psychogeographical resonance that brought the songs spontaneously to mind, or whether he compiled a virtual tape before he set out, and then silently repeated his musical mantra as he walked.

On the first floor, there is another text piece, 'Walking in a Moving World'. Beneath the title are six lines:

BETWEEN CLOUD SHADOWS

INTO A HEADWIND

ACROSS A RIVER

THROUGH SPRING BRACKEN

UNDER A BEECH TREE

OVER A GLACIAL BOULDER

They offer an unexpected, Haiku-like opening: the glacial boulder moves as cloud shadows do, and here is Long, the subject, another movement in a moving world.

I wasn't so keen on other textual works in the exhibition. 'From Simplicity to Complexity' lists short words progressing down the wall next to the vertical statement 'A STRAIGHT WALK ACROSS DARTMOOR'. It begins with 'ADRENALIN/HOOFPRINTS/LARKSONG', but soon, generalities start drifting in: 'AN IRON TASTE/SENTIMENT/A SNOOZE/SADNESS/HOT FEET/TUSSOCKS/REGRET'. I would have preferred greater verbal rigour: larksong, an iron taste, tussocks and even hot feet have a certain specificity and power, but not sentiment, sadness and regret. These latter are emotional shorthand, not observation.

Paradoxically, I enjoyed 'Ocean to River' almost in spite of the text. Under the large printed banner of 'OCEAN TO RIVER/WATER TO WATER' was the following small print: 'Atlantic water from the Pointe Espagnole carried across France on a walk of 473 miles in 16 days and poured into the Rhône river at Pougny-Gare at the end of the walk, spring 2005'. Sometimes, Long's actions speak louder than his words.

The top floor of the gallery contains three large sculptures. Standing in front of a piece such as 'Sardinian Cork Arc', looking at the textures and arrangement of the curls of lichen-shaded bark, gives a very immediate pleasure. And yet, these works, constructed from materials very far removed from their source, are somewhat at odds with the rest of Long's practice, which usually involves a minimal disturbance of the environment. The black and white print of 'The Time of Space' illustrates this: it shows a circle of stones on a gentle screen slope, arranged by Long on a three-day walk on Mount Parnassus in 1999. The caption informs us that he dispersed the circle on a six-day walk in 2002, thus creating 'A CIRCLE OF 1,114 DAYS'.

The sense of pilgrimage and isolation within Long's works and walks lend them power, but this is hard to achieve without selectively ignoring human presences in the landscape. So, it was heartening to find, in the text piece 'All Ireland Walk', amusing fragments like 'IT'S GOING TO BE BAD ALL DAY AND TOMORROW', 'FOLLOWED BY A DOG FOR FIVE MILES', and 'PLEASE LOOK FOR A LOOSE HORSE', giving a more balanced sense of a lived-in land. However, I still feel that there's an unresolved tension between Long's solitary walks through remote areas of the planet, and the display of the resultant art in urban centres. These are places polluted and pollinated, compromised and fertilised by just those factors his walking tries to escape: human contact, exchange and exploitation.

James Wilkes

http://72.14.207.104/search?q=cache:ESwWxq89V3wJ:www.studio-international.co.uk/reports/long.htm+richard+long+meaning+of+circle&hl=en&gl=us&ct=clnk&cd=2&client=safari

"If a new layer was revealed, it had to do, perhaps, with the spirit of the times: This group of objects seemed to be more about design than politics."

Frances Richard, ArtForum, Jan 2000

The best work is the sculpture of the siamese cup ("T 4 2" (2002)), two cup that blends one into another like a cell caught in the process of duplication. Obviously, this work deals with notion of clonage. I'm sure the fact the artists lives in England adds a special political resonance to the use of a teacup.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

Monday, May 08, 2006

The project consisted of an installation made with talcum powder swept on the floor.

Two rectangles were outlined on the floor with adhesive tape, which was removed at the end of the process. Some talcum powder was spread within these empty rectangles and then swept with an ordinary broom. A thin layer of powder was subsequently formed on the floor by the act of sweeping. After the adhesive tape was removed, the rectangle remained clearlty defined by this "coating" of white powder. The excess talcum powder was gathered into small piles that were placed just off-center, inside the rectangles. The traces of the broom remained present and tesrified to the act of sweeping.

THe installation was transformed with the passing of time as it incorporated the process of disappearance through the accumulation of daily dust, which slowly covered and blended with the layer of talcum powder on the floor, becoming one in the end.

The tones have a social and practical use. Frequencies at large are mostly unexplored.

How do they work? What effect do they have on life? The debate on whether cell phone frequencies can cause cancer and other

maladies continues, and we still don't even know what frequencies were used in collapsing the town of Jericho, what frequency the Chinese considered the "base" tone for life in general, or if the daily noise volume in cities has lessened our perception or our auditory abilities to listen to contemporary music.

The installation "Operation of Spirit Communication" enables people/ souls to communicate with the living, but it doesn't want to prove that souls are able to communicate trough these 13 sinewaves via radio frequencies. Rather, it wants to underscore alternative forms of function and usage.

It points out that everything is possible and that nothing is absolute.

-Carl Michael Von Hausswolff

"and" is a sculpture consisting of two 800pound limestone boulders that were placed on top of one another, with a steel pole acting as a central axle. A second pole was then inserted into the top rock, parallel to the ground-similar to a mill. She pushed the pole around in a circle five hours a day, for six weeks. With thses efforts, she achived a relationship in which the two forms resisted and gave into one another at an equal rate. She stopped grinding when the rocks beame interconnected.

_Janine Antoni, and , 1997-99

J Cardiff, telephone, 2004

consists of a recorded telephone conversation between the artist and a scientist on the nature of space and time. Form the point of view of a scientist, the disintegration of time and space is a very common theoretical paradigm. This collides with the traditional Kantian view of the "a priori" in a human-centered world-view.

But each person would have a measurable difference in time physically and emotionally.(people living different area having a different time notion at the same time)

so a person would be in multi-dimensions at the same time?

yes, in some sense.

One can observe that such a rapid shifting time rather then being a fluid gradual shift which would be more common in our daily lives, where our sense of time is changing very gradually so we don't tend to notice it changing.

If everyone is working at their own sense of time, then how can you have any consistent time, that isn't logical.

And this mean that there would be a multi-dimensionality going on constantly.

The Lorn Birds

Los pájaros perdidos

(Mario Trejo)

Amo los pájaros perdidos

que vuelven desde el más allá,

a confudirse con el cielo

que nunca maá podré recuperar.

Vuelven de nuevo los recuerdos,

las horas jóvenes que di,

y desde el mar llega un fantasma

hecho de cosas que amé y perdí.

Todo fue en sueño, un sueño que perdimos,

como perdimos los pájaros y el mar,

un sueño breve y antiguo como el tiempo

que los espejos no pueden reflejar.

Después busqué perderte en tantas otras

y aquella otra y todas eran vos;

por fin logré reconocer cuando un adiós es un adiós,

la soledad me devoró y fuimos dos.

Vuelven los pájaros nocturnos

que vuelvan ciegos sobre el mar

la noche entera es un espejo

que me devuelve tu soledad.

The Lorn Birds

I love the lorn birds

That return from far away

To melt into the sky

Which I shall never be able to regain.

They return once more, the memories,

The hours of my youth I spent,

And from the sea emerges an apparition

Of things once loved, then lost.

It was all a dream, a dream we lost,

As we lost the birds and the sea,

A dream as short, as old as time,

That the mirrors can’t reflect.

Ever since I’ve tried to lose you in so many others,

And that ‘other’, and all, were always you;

At last I’ve come to understand when a good-bye is a good-bye,

Solitude consumed me and we were two.

Returned once more, the birds of night,

That fly blindly over the sea.

The whole night is a mirror

Casting back your solitude at me.

Sound Gardens

Here is something that has been around for some time as an idea, with a few small-scale realized projects - but now it seems to be growing quite fast.

The Tactical Sound Garden is an environment (i.e. potentially a physical space of any city) where users of devices such as iPods and other portable sound systems with wireless communication can discover the sounds implanted by others.

In practice this means one walks into a space and hears different sounds. As one moves along, the sounds (songs, noises, voices?) change, new ones appear.

The Tactical Sound Garden [TSG] Toolkit is a vehicle for exploring this via the design of an infrastructure: an open source software platform for cultivating public "sound gardens" within contemporary cities. It draws on the culture and ethic of urban community gardening to posit a participatory environment where new spatial practices for social interaction within technologically mediated environments can be explored and evaluated. Addressing the impact of mobile audio devices like the iPod, the project examines gradations of privacy and publicity within contemporary public space.

Several interesting points about this sort of developments:

- A walkman stops being a synonym of alienation. It can become a shared experience.

- The trust in human goodness is boundless. As the average age of an iPod user (or, what's more significant, a "qualified user") drops, these Gardens, invisible to a common passer - by who might have pu social pressure to keep it tidy, can very well become depositories of some of the most uninspiring sound garbage. ("NOT INCLUDED in the Toolkit are regulations for governing the use (or abuse) of the garden. This is left to the gardeners to sort out. TSGs are intended as self-organizing systems.")

- The audio part of space suddenly becomes a brave new world. It will create specific, isolated communities that are a gem to any advertiser: they have money and time to spend. I wouldn't be surprized, then, if this artistic endeavor soon took on a new twist and became a sort of a commercial radio, where one can discover the wonderful soundscapes for the modest price of having them brought to you by "Chico-Chico, the chocolate that makes it all sound great".

- What exactly is a sound garden? Or rather, what can it be? Are there some possibilities we haven't thought of yet? Rhythms? Conversations? Plays? Games? Dances in public spaces? Lessons? What else?

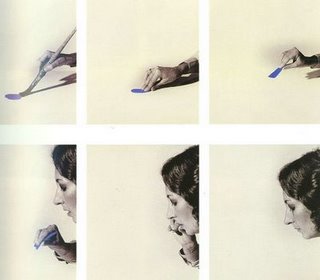

Helena Almeida, Dentro de Mim, 1998

I have never come to terms with canvas, paper, or any other support. I believe that what has made me come forward out of these elements through using volumes, shapes, and stringis my deep dissatisfaction with problems of space. Either by facing these problems or refuting them, they have become the one constant of my work. I believe that I can say now that I paint paintings and that I draw drawings. It is not a question of exhibiting but rather exposing, and also of being able to communicate more deeply the ideology and character of "art"-acceptiing it and therefore being able to deny it.

Through photographs within drawings I believe that the same denial is made in a variety of ways. What I am exposing is not the "artist's imprints" but rather the representation and the denial of these imprints.

This denial means a rediscovery of another space while it also tumbles into another poetic trap. this happens because by placing myself as the "artist" in a real space and the spectator in a virtual space he exchanges imaginary space.

To become an unreality. To become an appeal to the possession of intimate joys. TO become at rest as in the drawings. To live the warm interior of a curved line. To meet again the peace of an inhabited drawing.

-this text was first published in conjunction with a solo show of the artist's work in 1976 at the sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes, Lisbon, Portugal.

Only small sones roll along in the water; the big ones let the water go by.

-spoken by a navajo indian in a dream

making map

I am saying you will have doubts.

If you do the best you can you will hae no trouble.

When you try to find a place for it-a place not too obvious, not too well hidden so as to arouse suspicion- you will begin to understand the furility of drawing maps.

A place where nothing has ever happened.

Tell him you wish to see the place for yourself.

You may never again hear a map so well spoken.

Prepare for the impact of nothing.

On the third or fourth day, when you are ready to quit, you will know you are on your way.

You will always know this: others havd made it.

He can make a very good map with only a napkin and a broken pencil.

He knows how to avoid what is unnecessary.

beyond east and west