In April, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts had its second exhibition of sculptures by Roxy Paine, a young artist whose work is some of the most exciting around. It speaks to the artist's role as maker, and to the sort of making, in variety and difference, that is his provenance. Paine's work connects artmaking to the theoretical and logistical methods employed passively by the artist in creating an active art object. Paine insists that his work is about nature and its potential. This recalls Harold Rosenberg's essay "The Anxious Object," which describes how any artwork which is opaque can work off of the viewer's anxiety to suggest ideas. In Paine's case, that idea is a sense of the mode of communication being formed. This language is invented in three ways: by an attempt at the organic simulacra; an organizing of abstract aggregates; and by a mechanically repetitive action.

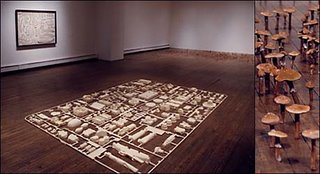

The first thread of Paine's work is represented by mushroom field (1997) and poison ivy (1997). These works study the superficial and structural edifice of natural organisms. In both mushroom field and poison ivy, he assimilates the multiplicity and organic density of living matter. Both are just what they describe, images composed to as to immediately mirror the surface design of nature's own idea. mushroom field is set upon the floor, two thousand individual models for real-life psilocybin mushrooms, each drawn out and designed with variations of color and growth patterns, as well as the wavelike pattern of the field as a whole, covering an area some ten or twenty feet in diameter. The effect is quite unsettling, of encountering these realistic lifeforms sprouting from the dead wood floor of the gallery space. It is almost hopeful in such a stance. It suggests that the gallery takes part in the in the growth of the artist, or the art in general. In poison ivy, the attention for detail is the same, but the approach is different. Instead of building a natural manifestation into the gallery area, he has collected living poison ivy plants and planted them inside a glass-enclosed patch of ground, along with versions of the self-same plants which he has fabricated.The effect is one of puzzlement, even of wonder, but a certain degree of encounter has been eliminated in placing these specimens under glass. They can no longer exert an effect upon us via their touch or proximity to us, or through our anxiety related to this particular plant.

model painting (1996) and model for an abstract sculpture (1997): both represent a system of communication developed solely by Paine, edited and constructed like hieroglyphs. In the first, he has been able to isolate solidified flesh-colored polymer brush strokes; in the second, he has accumulated various blister packs. Blister packs are part of the refuse of daily life, something which Paine has been able to utilize with regard to ideas of both positive and negative space inherent in their forms. In other words, it's initially difficult to view them as forms created to wrap around other forms. But within their model skeleton they approach a sense of anatomy, of social and political connections between shapes. Each pack then becomes a house in a town, a cell in a body, or a symbol in a system of scientific order. However, the objects accumulated with these works are neither mere simulacra nor Dadaesque mind-games made flesh. The shapes of the objects, if they can be called that, whether blister pack or polymer brush-stroke, suggest only the vaguest of forms, creating an inventive and playful acrostic of formal origin. Their organization is the creation of the new language being formed in us.

The third and final thread of Paine's work is represented by paint dipper (1997), a machine constructed to create paintings by a slow and methodical process. The canvasses hang above a vat of thick white house paint, which is timed to open and dip them down to a certain measured point every few hours over the duration of twenty-four hours. It moves so slowly that rarely does the spectator actually see a painting being dipped, but as it hangs there, dripping paint off onto the machine and the floor around it--completing the process for which it was built--it is fusing ideas of natural formation with inorganic production, and this points out the limitation of the machine. By the manner of its manic and regular action, a process of ambiguous signification surfaces, one which can also be seen in any of the other works here, a negation of individual creation that when taken to an extreme creates a force of juggernaut proportions. This is the activity into which each of us falls when we try to compensate for the stultifying complexity of creative demands. Thus, paint dipper shows itself as eerie proof of our inability to contain or answer the complex demands of everyday life. All that the artist retains is his individual and idiosyncratic vitality. Paine's work is never dependent upon the forms invented in nature, but in forces directly supervised, and to some degree invented, by the artist. His control of them is both his freedom and ours.

David Gibson

New York, New York

1997

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home